Little Cities of Black Diamonds

The early settlers and surveyors noted the outcrops of coal along streams in the eastern part of Ohio. While entrepreneurs recognized its economic value, there wasn’t yet a means with which to ship the coal out of the region to cities and industrial hubs.

That began to change in the 1830s and 40s with the construction of canals. The Hocking Canal reached from Lancaster to Logan, Nelsonville and Athens, but due to flooding, freezing and the slow pace of canal boats it was never really a money maker. Therefore, by the 1850s, investors had begun exploring rail as an alternative. Early construction efforts were impeded by the Civil War, but as the war ended capital became available to build a railroad connecting Columbus and Athens.

By 1869 the track reached Nelsonville. At this point, between the canal and rail access, Nelsonville had experienced rapid growth. In a newspaper article, it became the first town to be referred to as a “little city of black diamonds.”

The following year, the railroad reached Athens, and immediately investors began construction on a 13-mile “Straitsville Branch.” What they were after was an extraordinary vein of coal, referred to as the “Great Vein,” that was estimated to be 12 to 14 feet thick. Thus, the village of New Straitsville, founded in 1870 and connected by rail in 1871, became the region’s first “boom town.” Within the next 20 years, over 70 coal towns and camps sprung up in the surrounding hills, following the path of the coal and of the railroads.

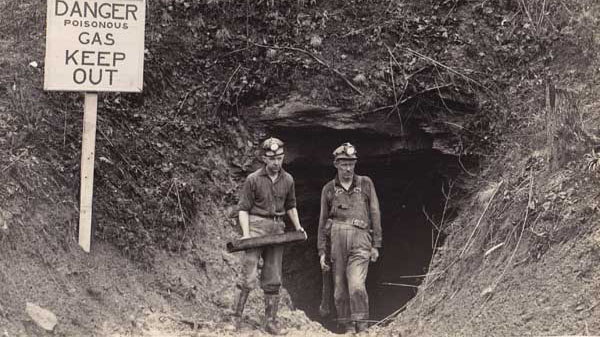

The surge of new mines required a surge in laborers to work those mines. Investors began actively recruiting skilled miners to settle in the region and help them extract coal. Recruitment campaigns stretched as far as Europe, where agents would paste up posters and give pitches to immigrants before they boarded ships to America. Other agents were stationed in American ports and would escort new immigrants onto trains headed for Ohio.

One of the biggest sources of labor in the early days was the British Isles. Coal mines had long been a part of life in England, Scotland and Wales, but miners were becoming disgruntled with their lack of representation in the British government. In Great Britain, no man was entitled to a vote unless he was a landowner, while the United States granted votes to any white man, whether he owned his land or not. Prominent figures like Alexander Macdonald encouraged miners to immigrate to America where they would find better representation. Because these men were already skilled miners, they were prime recruits for the enterprises starting up in the little cities.

As a result, the labor movement was present in the little cities even in the earliest days of the mines. Most of the men who arrived in the region had already been active participants in the unions of their homeland, and they quickly organized in their new communities. By the 1880s, the immigration pattern changed and settlers began pouring in from other parts of Europe, including Italy, Germany, Hungary, Poland, and Czechoslovakia. The unions made a point of recruiting these groups as well. Union demands directly conflicted with the interests of investors, who believed that the best way to ensure profits was to keep costs low, and that the best way to reduce costs was to lower wages.

The unions were strong and highly effective at putting pressure on mine owners. Not only did they orchestrate strikes, which slowed or halted production, but they also cost the mines valuable resources. In one notable instance, miners burned out the Bristol Tunnel in order to prevent trains from transporting coal out of the region. Labor disputes also inspired the setting of the New Straitsville mine fire in 1884 and 1885 (a fire which still burns today), although it’s asserted that the fire was set by dissenters, not union operatives.

Another force that influenced mining in the little cities was the rise of mechanization. The first mining machines in the area were made by The Jeffrey Company out of Columbus, Ohio and arrived as early as the 1870s. Machines reduced the demand for labor from 600-700 men per mine down to just 200-300. Even though labor was reduced, machine mining entailed its own costs, since a mechanized mine requires continuous power to run the machines.

Three forces ultimately led to the downfall of the coal mines in this region. The disruptions of the labor movements made some mines more trouble than they were worth. The expenses of mechanization ate into profits. And, over time, the successful harvesting of coal eventually meant that there wasn’t much left to extract. By the 1930s, investors were no longer interested in running large mines in the region. Those that remained after 1930 were small, worked by 10 or 12 men or were transitioned into strip mining operations.

Have a question about history in the Little Cities of Black Diamonds Region? Reach out to one of our historians!